ERIC LEYLAND: HACK OF ALL TRADES by Jim Mackenzie

A short study of the range and variety of the titles listed under Eric Leyland's name (and his various pseudonyms) makes you quickly realise that we must take his own self-deprecating estimate of his talents as a "competent hack" with a pinch of salt. Anyone who can produce over 320 books for so many different audiences shows a fertility of imagination and an appetite for work that can only be admired. Just take the matter of book length as a criterion – the various publishers that Leyland worked for during his career all placed different demands upon him in order to fit their pre-determined formats. A random selection of his titles shows you what I mean:

The Steven Gale series for Frederick Muller and Co are all required to finish within 172-176 pages whereas the Abbey Books for the Nelson Triumph Series have 212 pages as their target.

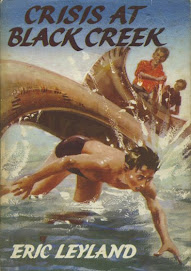

The books in the Hunter Hawk series (published by Edmund Ward) all finish on page 127 or 128 whilst a title like Crisis at Black Creek for the Nelson Peerless series is completed in 88 pages. One of his earliest efforts Treasure in Devon (Blackie and Co) stretches to page 254 and when he assumes the mantle of Nesta Grant for the Burke Falcon Library his required quota is 224 pages. Outlaw Gulch, way out west for Spring Books, weighs in at 200 pages and the Flame series for Hodder and Stoughton matches W. E. Johns 1950 Biggles books at 190 pages.

That's eight different lengths from just this small selection!

But notice also his versatility – we have already listed six or seven different genres of writing:- the boys' school story, the girls' school story, the aeroplane adventure, the western, the free-lance secret agent mystery, the young boy's mystery adventure for ten to eleven year olds, the older boys' mystery adventure for 13-15 year olds, and the boys' adventure story which features a grown-up newspaper reporter as the central hero. It takes a considerable amount of skill and a tremendous capacity for self-discipline to constantly serve up what is required in this way and still manage to tell a reasonable story.

Enough of these figures – what is he actually like as a writer? The answer, unsurprisingly, considering the volume of his production, is good, bad and indifferent.

Crisis at Black Creek is a good example of Eric Leyland writing a short adventure for ten to eleven year old boys. There is no doubting the masculine nature of the book for not a single girl or woman is ever mentioned. In spite of the title and the American setting this story is not a western. It is set in California and concerns the adventures of two English boys who go to a summer camp set high in the mountains. Two of Leyland's virtues as a writer can immediately be seen – he knows how to start a book in a gripping fashion and he knows how to hold back surprises as he unravels a mystery.

Within five short pages the reader has established that Tony and Dick are stuck on a train in the middle of the Californian hills, are involved in a fight with an older aggressive American boy and have been called thieves into the bargain. When the same American boy plays a malicious trick on them and promises trouble at camp the reader is already feeling apprehensive on their behalf. The dialogue has been sharp enough to play upon traditional Anglo-American hostility, where the comment:

"Got a bad habit of thinking you own the world, haven't you?"

brings the riposte,

"You want to read the newspapers sometimes, chum, and then think again. You've been telling the rest of us how good you are for years!"

It little matters which outburst is said by the English or the American boy for each comment is designed to set the teeth on edge. There is no jingoistic side to Leyland here – both boys at this point are equally to blame for losing their tempers. They are both gloriously unreasonable.

Events at camp follow on this bad start at a cracking pace with an unprovoked attack in a canoe and the loss of a valuable watch. Having clearly established the "good guys" and the "bad guys" amongst both the boys and the camp counsellors, Leyland then cleverly mixes it all up. The two boys who were about to knock seven bells out of each other in the boxing ring suddenly become allies in the face of ruthless enemies. The person you started to suspect is actually a private detective, and the man you thought was above suspicion isn't. There is even a short explanation scene in the style of Sherlock Holmes where Tony points out the errors the chief villain made. Looking back at the clues he mentions, you realise you should have spotted them but the pace of the book hurried you past before you could notice.

As you might expect in such a short book there is little room for character depth or character development. Similarly the scenery is functional rather than convincingly realised. Apart from the discovery of oil-bearing strata (the secret reason behind all the villains' plots) the story could well have been set in any of the American states that has a mountain. Remember, however, that it was only 88 pages long as per the Nelson Peerless requirements.

Now let us look at one of the character series at which Eric Leyland became such an expert. We move to the seven volumes concerning the adventures of Hunter Hawk, Skyway Detective that he wrote in collaboration with T. E. Scott Chard between 1957 and 1962. The idea of a flying detective was, of course, not new. Many famous writers for boys from Percy F. Westerman to George Rochester have written about air investigators. Without doubt the most famous during the 1950s was Biggles of the Special Air Police as envisaged by Captain W.E.Johns.

Eric Leyland knew W.E.Johns personally and he certainly knew what he was taking on when he launched his own series alongside the most famous fictional pilot of all time. Perhaps he hoped to pick up some reflected glory and his publishers (Edmund Ward) probably saw an opportunity to cash in on the insatiable appetite of the air-minded youth of the nation. Hodder and Stoughton had already promoted the Flame series by Leyland on the dust-jackets of the Biggles series and so the practice of one boys' series spinning off another (even by a rival author) was not unknown.

Investigators require cases and writers are required to make each case different in its details from the one that preceded it. Naturally the readers expect a blend of clue solving and rapid action each time the detective starts on a trail. Some parts of a formula are traditional, indeed compulsory, but there has also got to be a novelty that offsets the predictable. Once again Leyland with the Hunter Hawk series is to be congratulated on the way in which he comes up with seven very different yarns.

Even the titles have a satisfying ring to them, from the alliterative Smugglers of the Skies and Commandos of the Clouds and Outlaws of the Air to the enigmatic The Atom-Plane or Bandit Gold. The experienced reader of boys' or even adults' adventure fiction will recognise the plot-drivers that are about to be listed. There is the theft of gold and other precious metals from a British Airline; there is the sabotage of a new aeroplane on its proving flight; there is the involvement of air power in a South American revolution; there is the secret weapon that could bring world destruction and there is the search for lost Nazi gold. Leyland handles them all with aplomb and competence, making perhaps the best fist of the gold theft story in Outlaws of the Air.

If T. E. Scott-Chard, the aviation expert from BOAC, was responsible for providing the technical aeroplane details, then Eric Leyland certainly made first-class use of them in the way that he describes flights during the course of the books. Even W. E. Johns, much to his chagrin, got it wrong on many occasions and sometimes owned up when his readers caught him out. In particular the references made to the types of plane and their endurance range can prove tricky subjects when taking your heroes to far-flung aerodromes in Malaysia or South America. Leyland never makes any obvious mistakes and is never deliberately vague about technical details. In Outlaws of the Air there is a very impressive description of a Proctor caught in a tropical storm and then suffering from an unexpected attack by a war-surplus Japanese Zero. After reading this account you would feel confident that if you crash-landed in the sea you too would know just how to get out of the cockpit quickly and safely.

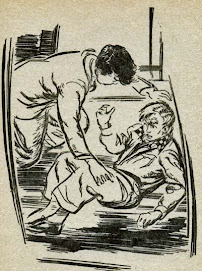

To extend the comparison with Johns still further, it is clear that Hunter Hawk and assistant and cousin Mike bear a passing resemblance to Biggles and his protégée Ginger. Hawke is an R.A.F. air ace and Mike even has red hair, just like the aforementioned Ginger. However, the difference is that, whereas Biggles and his team avoid physical contact with the enemy and very rarely indulge in fisticuffs, Hawke and Mike are presented as ring-hardened and constantly relishing hand to hand combat:

"He took the man from behind, ducked down, so that he was crouching, and jerked the fellow over his shoulder. He went over Mike's shoulder as lightly as a feather, and fell on the back of his head, his body coming over so that it pivoted on the neck, the head at an angle on the floor - and crumpled up in a heap against the wall."

Descriptions like the above are a recurring feature of the Hunter Hawk series, though it has to be admitted that the two heroes come in for their fair share of knock-outs and waking up in back alleys or darkened rooms. This sort of appetite for violence is found only in W. E. Johns' Gimlet books and shows up very rarely in the long Biggles saga. Mike's impatience to get to grips with the "ungodly" as they are constantly called is, at times, overwhelming. The normal emotions of fear or self-doubt which can make Biggles or Ginger seem like real human beings are not explored. Mike and Hawke are always "up for it" and thus have an air of invulnerability that makes them distant from the readers.

Inevitably Leyland deploys two types of villains not uncommon in all juvenile mystery literature. There is the clear obvious opponent, usually one of the small fry that follows the hero and gets into minor tussles from even the early pages of the books, and there is also the concealed "big boss" who comes as a surprise near to the end. The observant reader will soon cause Eric Leyland's stories to suffer from the law of diminishing returns. You quickly learn with the Hunter Hawk adventures (and lots of his other ones) that the person you should least suspect is the one most likely to prove the villain. Leyland has no need to worry about this for most readers will be content to swap the pleasure they get from the "surprise" ending for the smugness they can feel when they spot in advance what is about to happen and are shown to be proved right.

The Steven Gale series, where once again a grown-up hero takes the lead in a boy's story, has a similar preoccupation with physical violence as the intrepid reporter pursues various exciting scoops in Britain, Europe and round the world. A large part of Gale and the Sword of Mars is concerned with fighting a gang of criminals in, around and underneath a castle in Austria. How to disable the other chap and get hold of his gun or his car is the main preoccupation of the story. However, this time the fair sex is allowed to make its appearance in the form of Steven's secretary, Judy Watson. She is attractive, resourceful, courageous and has a generous spirit, even giving away a castle she won in a competition so that refugee children can have a home. At one point we have the following scene:

"The next moment she was in his arms, her breath coming in gasps. She was shaking.

"It's alright, it's me, Steve."

"Steve!"He held her gently, his arm round her slim shoulders.

Leyland can't seem to make up his mind whether to allow a romance to happen or not. In the end he opts for the "just good friends" approach where Judy comes in for some good-natured flirtation and joshing from Gale's nephew and his friend. The crunch comes when Judy is given this rejoinder by the author, "I'd take it as a favour if you'd stop hinting that I like Steven more than I really do . I hope I've managed to get that into your thick heads?"

So much for romance. However, we must not forget that Eric Leyland had several feminine incarnations where he wrote girls' school stories. Strangely enough,The Strange Affair at Abbot's, which he created under the guise of Nesta Grant, produces some of his best writing, including an effective and engaging depiction of a heroine. Penny Webster, just over seventeen, was dark and attractive and her friend Hilary is blonde and just as slim and vivacious. Eventually they were destined to become "charming and efficient young women" but, and here Leyland starts to capture the humorous tone that eludes him for so many of the other books,

"At the moment they were rather efficient at the wrong things." He follows this suggestion with another attempt at defining their irrepressible but irresponsible spirits. "Penny and Hilary did not shirk their duties, but they were not exactly earnest about them."

In other words, the two girls walk the narrow line between enjoying legitimate fun and becoming a liability to themselves, their family and their school. Enter Frances, their friend, who was entirely different in temperament and who "felt it necessary to attempt to guide her friends' wandering footsteps on to the straight and narrow path."

For a while Leyland shows how opposites attract and then, with a subtlety that has not been evident elsewhere, he precipitates a drastic change in their relationships. Frances is made into Head Girl of the School much to the surprise of everybody concerned, including Frances herself. After all "Frances was charming, Frances was clever – but she was not a leader."

Penny's reaction to this news is characteristic: "Frances! It doesn't make sense. She couldn't say boo to a goose."

From this point onward the story starts to exert a real grip for the reader is encouraged to take sides with both Penny, the high-spirited outlaw, and with conscientious Frances coming to terms with her new responsibilities. The way in which Leyland makes the trivial assume an unprecedented degree of importance is cleverly done and this is well illustrated by the election of the cricket captain episode. Here, poor Frances, who has to chair the committee making the different house appointments, is preoccupied with all sorts of details. Having gone off into a "brown study" of worry, she believes that Penny has already been elected cricket captain unanimously and that she is voting on the issue of who is to be tea secretary. Thus she allows a totally unsuitable candidate's name to go forward. Penny wins the election safely but can never forgive Frances for her apparent support for another girl. From such small misunderstandings a form of enmity grows and the inevitability of fate means that Penny, without really meaning to, begins to undermine Frances' authority.

Cunningly, Leyland uses Hilary, the third point in this friendship triangle, to help shape the reader's own views of the correct morality. Still devoted to her friend, she starts to have misgivings about some of her wilder adventures. She has to ponder deeply upon the right course of action. The writer has succeeded because he has started to make his readers think about what is the right thing to do. Take the issue of the cricket match – should the troublesome junior who has been given detention by Frances (against all the school traditions) be encouraged to skip her punishment to play in the vital cricket game because she is a devastating bowler whose talents are clearly needed? This multi-layered approach is a refreshing change after the simple black and white morality of Hunter Hawk or the Steven Gale Adventures.

What a pity therefore that The Strange Affair at Abbot's should include a secondary plot about the theft of a Shakespeare Folio that is much more in line with his usual adventure format. Leyland tries to take the sting out of this improbability by authorial comments, "Melodramatic, you may think. Certainly, but then Penny had a melodramatic mind."

This is a good try at wriggling out of the mismatch of plots but not quite good enough. This principle of attacking yourself before others do so does not quite work on this occasion.

The unfortunate habit of combining the school story with a rather sensational adventure story is a problem that seems to dog his footsteps in his boys' school narratives as well. The blurb for Abbey Sees it Through poses some very intriguing questions:

"When two great public schools amalgamate there can be only one captain. Must the other step down in enmity ? Bill Forbes of Abbey School has his supporters and, of course, Dick Manners of Brancaster has his. So what will happen?"

This is a very sound basis for a plot and, like The Strange Affair at Abbot's, Leyland pursues this idea with some panache and subtlety for several hundred pages. The establishing of a new pecking order and the working out of inter-school resentments gives Leyland plenty of scope for enjoyable confrontations and interesting character development. But why did he have to include an unconvincing sub-plot about an escaped convict and destroy the plausible atmosphere he was at pains to build up so diligently?

"I don't believe it!" muttered Bill. "I just don't believe it"

So far as the convict adventure is concerned we are forced to agree with Bill.

Before we conclude this survey of Eric Leyland's fiction it is worth mentioning firstly his writing in the juvenile western genre and his writing for much younger children. Outlaw Gulch in the Halcyon Library series is an attempt to write about a series of gold robberies in old Arizona. The usual Leyland action sequences and plotting are there and, once again, the reader is plunged into action within a few pages by the description of a stage-coach robbery. This time the problem is with the proliferation of hero characters, for the writer attempts to keep us interested in the doings of no less than three Texas Rangers. Unfortunately we get no sense of place or personality and the story relies entirely upon having things happen all the time. Motivation is not deeply explained and so it is perfectly possible for anyone to turn out to be the villain. True, he can still produce the surprise twist in the plot, but this relying upon superficial descriptions of people to allow him to reverse our expectations is ultimately sterile. The flavour of the Wild West is conveyed by dialogue which is riddled with "guesses" and "reckons" and "figures". One only needs to read the Pocomoto series by Rex Dixon to see how inferior Leyland's product was in this area.

One cannot do better than end this evaluation by considering Crash Landing, published by Brock Books. It is clearly aimed at a 10 to 11 year old market for boys and contains some of the best and the worst of his writing. If we boil it down to its principal ingredients, it is a story about gliding and about smuggling. The two chapters in which Tony (a favourite character name of Leyland's) does long-distance gliding with his Uncle Mick are fine and exhilarating. The remaining section in which the use of gliders to smuggle diamonds out of the country is laboriously plotted and is even more implausible than usual. The identity of the background villain is no surprise and even the least advanced of readers will have guessed that the glider contains the missing stones long before this fact is produced as a great surprise. Perhaps young readers need this sense of safety, this comfort that they know where the book is heading long before it gets there. Those writing or reading this review are now too old to judge.

As we draw to the end of the survey, the blurb on Wings Over the Outback, one of the Max and Scrap series for younger readers, gives us a timely reminder of where this author's main contribution to children's literature lies. "Widely travelled, especially in Europe, he has played nearly all sports; Well known as an author, he has written over 100 [Note the underestimate!] books and contributes to many children's magazines and a host of annuals."

Space and time do not permit every aspect of his varied writing life to be evaluated. His role as an editor has not been considered, nor have his contributions in the field of non-fiction. Though he showed some considerable knack for the development of character, situation and humour in the best of his school stories, Eric Leyland's place in juvenile literature is best measured in terms of the breadth of his interests and the pace and variety of his books rather than by the depth of the emotions that he captured. He was a more than competent writer who chose volume rather than quality. Read The Strange Affair at Abbot's by Nesta Grant and you can spot what might have been had he chosen another route.

Wednesday, 8 April 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)